October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month.

Defined as “a pattern of abusive behavior in any relationship that is used by one partner to gain or maintain power and control over another intimate partner,” domestic violence (DV) can be physical, emotional, sexual, psychological, economic, or even technological in nature. More than 10 million American adults experience DV annually: It’s a social issue prevalent in every community without regard to gender, age, socioeconomic status, religion, race, nationality, or sexual orientation.

Research shows that DV impacts the LGBTQ+ community at rates similar to heterosexual individuals, and that it can be equally underreported. Consider:

- 26% of gay men and 37.3% of bisexual men have experienced, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime, in comparison to 29% of heterosexual men, according to NCADV.

- In a study of male same sex relationships, only 26% of men called the police for assistance after experiencing near-lethal violence, according to NCADV.

- Transgender victims are more likely to experience intimate partner violence in public, compared to those who do not identify as transgender.

- 43.8% of lesbian women and 61.1% of bisexual women have experienced physical violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime.

Wondering how to recognize the signs of DV, why it closely intersects with HIV, and what you can do to help yourself or another victim in crisis? Read on to learn more.

First thing's first: Awareness of DV is key

For decades, domestic violence prevention advocates have touted the tell-tale signs of DV, including isolation, power, and control. Domestic Violence Awareness Month was founded in 1987 to educate people about this all-to-common experience that impacts one in three women and one in four men. Yet, only 55% of Americans claim to know someone who has experienced DV.

Ralston Lockett, APRN, FNP-C, a Q Care Plus nurse practitioner, acutely recognizes the need for DV awareness, especially in the medical community.

“We had a patient who reached out for PrEP,” Ralston says. “Through talking to them, we learned that their partner was taking advantage of them and they were experiencing violence at home. This patient also came back positive for a few STIs. They were presenting some symptoms that needed immediate medical attention, but they were afraid to go to the emergency room because of their partner.”

Because clinicians are often the first point of entry into difficult conversations about patients’ physical and emotional challenges, Ralston recognizes the importance of knowing the signs of domestic violence. “The goal is to ensure that patients have that safe space to always reach out, get that education, and get support,” he says. “They may not display physical signs of violence, but we can ask ourselves ‘what emotional disruption could be occurring?’ and go from there.”

Because Ralston’s care team at Q Care Plus keeps a pulse on various state resources, updated legislation, and other information that may be helpful to patients who disclose abuse, they eventually connected the patient to vital resources designed to help break the DV cycle.

“One thing that I have always focused on in my care as a provider is that each individual we’re talking to is a human at the end of the day,” he says.

Look out for love-bombing, power, and control

A host of warning signals often present themselves when an individual is experiencing an abusive relationship.

Joli Ienuso (they/them), M.Ed., is a former violence preventionist at Columbia University. They know through their own experience that power and control are at the center of most abusive relationships. “Of course, the complicated factor is always power,” Joli says. “There are times when, because of a power imbalance in relationships, coercive behaviors are at play. That is not consent. If there are these hierarchical or other sort of social power situations going on, that’s not consent.”

Experts also warn against love bombing.

“Love bombing is when a relationship is moving at a fast pace,” says Cindy Luquin, a certified sexuality educator and domestic violence survivor, “Your partner wants to know everything right away, they are expressing intense and fast feelings. You might like the attention, but those intense declarations of love are often a red flag.”

Cindy offers up as an example when someone she had been in a relationship with for only a few weeks told her they’d been, “waiting for someone like you my whole life.”

Love bombing typically happens at the beginning of a relationship. “It puts you in a place where you lose your sense of boundaries,” she says. “When you express your boundaries and they are reciprocated, that’s when you know you can trust someone.”

Other warning signs

Cindy is quick to warn people that “domestic violence is not only physical, but it could also be emotional, financial, spiritual, and other ways.”

Apart from love bombing, “isolation is a big one,” she says. “It’s not immediate; it’s slowly chipping away at your individual life until your whole identity is centered on the relationship. Financial abuse is another way. Someone could ask you to exchange part of yourself or stay in a relationship because they are financially supporting you. Those are two methods people use to keep you in an unhealthy relationship. You start to get afraid. You start to lose your voice. The important thing is to reach out for help.”

Joli suggests that individuals connect with their bodies a bit. “If you’re experiencing anxiety around or having chronic discomfort around the person you’re in a relationship with, it’s a sign that you are not in the relationship that best suits you,” they say. “The truth is, somewhere in us, we are likely to know.”

The LGBTQ+ community and relationship abuse

LGBTQ+ people experience relationship abuse at the same rate as heterosexual individuals. But, due to the stigma that abuse only happens to cisgender women, there is limited information available.

“There is more room for research,” Cindy explains. “We hear about DV mostly in cis-hetero relationships. But we know LGBTQ folks, especially trans folks, experience violence as well. Your identity is not going to make you exempt from experiencing human interactions, which includes unfortunate things like domestic violence.”

LGBTQ+ individuals are also at a higher risk for vulnerabilities like housing insecurity and lack of family support, both of which are risk factors for domestic violence.

“Let’s say you are experiencing housing insecurity or financial insecurity, and someone comes in and wants to help you,” Cindy says. “They can almost seem like a savior. But if you are unaware of negative relationship dynamics, you can quickly lose your sense of boundaries and individuality by putting your full trust in someone. And that could lead to a lot of missed red flags.”

Stigma impacts the rate at which DV victims seek assistance. “Due to stigma, people are less likely to take violence in LGBTQ+ relationships seriously,” says Robin Pereira, a program specialist at the National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV). When you hear about two women in a relationship together experiencing domestic violence, we think, ‘Oh they’re catfighting.’ When we discuss violence in the male community, we often talk about privilege. But how does that work when two men are in a relationship? These are things we need to talk about more. Stigma is dangerous when it comes to violence because it leads to people not seeking the help or resources they need.”

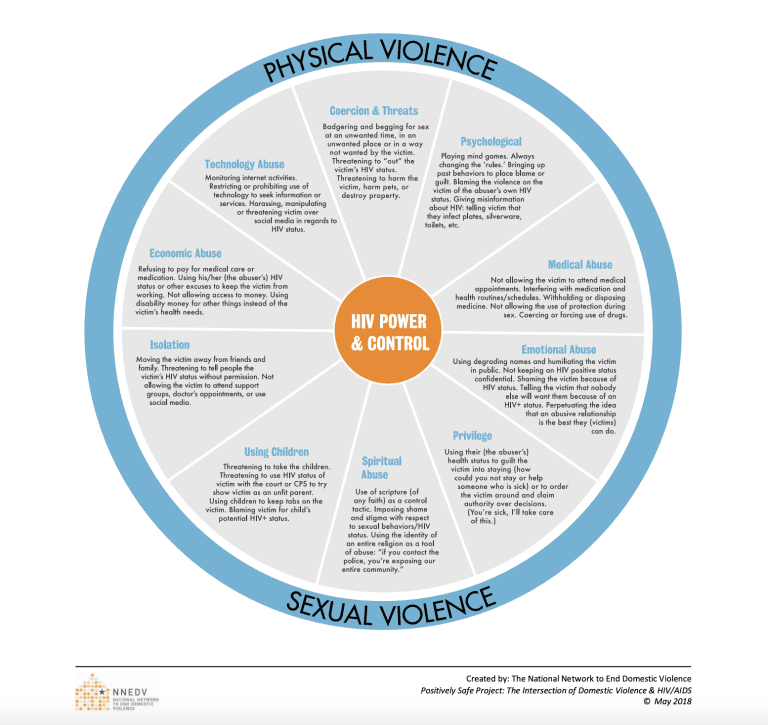

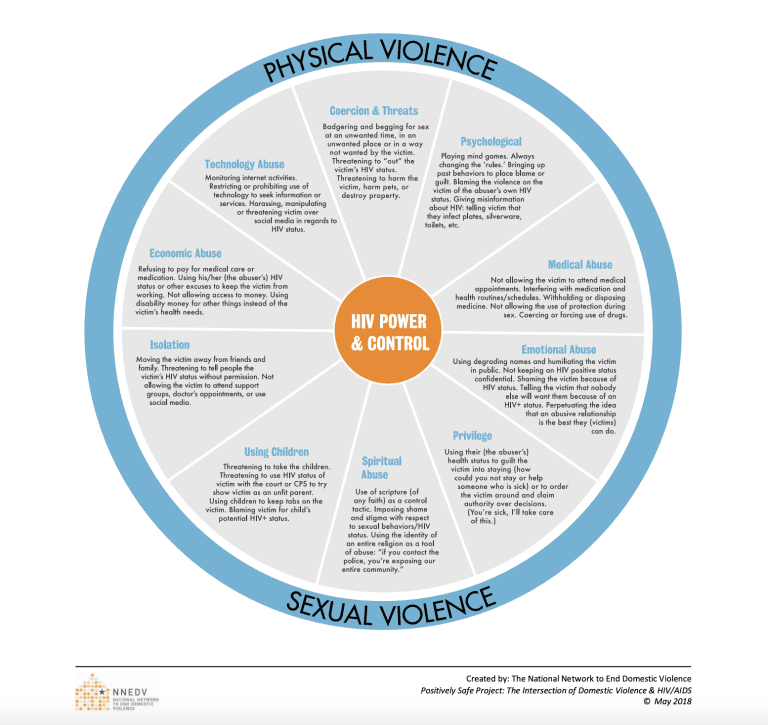

Why HIV and STI status can be a tool of DV

Unfortunately, abusers often attack insecurities or parts of a victim’s identity that are stigmatized to maintain control over them. Leveraging an abuse victim’s HIV status is a prime example of this.

“Fifty five percent of women living with HIV and 20% of men living with HIV have experienced domestic violence,” Robin says. “Folks who experience domestic violence are 48% more likely to be exposed to HIV than those in nonviolent relationships.”

With such alarming statistics, you might think the link between DV and HIV would be the focus of many public health organizations. However, NNEDV is one of the only organizations in the country with a dedicated program at the intersection of domestic violence and HIV: The Positively Safe program.

When it comes to signs of violence for those living with HIV, there are specific warning signs to look out for.

“We’ve seen many people whose partner does not allow them to attend medical appointments alone,” Robin says. “The abusive partner comes to appointments with them or just doesn’t allow their partner to seek treatment at all. That way, the victim doesn’t have a safe space with a provider to disclose abuse.”

“Maybe someone would like to get on PrEP or take an HIV test, but an abusive partner will prevent them from doing so,” she adds. “An abusive partner might go to the pharmacy and pick up an individual’s PrEP or HIV prescription so they can’t take it. They may destroy or tamper with PrEP or HIV medication. These are all ways that HIV or sexual health can be used as a tool for abuse.”

It’s also important to note that “an abusive partner may threaten to expose someone’s STI or HIV status to friends, family members, community members, or even children,” Robin says. “This can give a survivor a reason to stay in a toxic situation.”

Here are other ways STI/HIV status can be used in instances of domestic absuse*:

- Threatening to use a victim’s HIV-positive status as grounds for parental custody

- Sexually humiliating or degrading a victim for having HIV

- Isolating a victim on the basis that they pose a threat of infection to others

DV prevention for those living with HIV

Robin encourages her clients living with HIV and in an abusive relationship to use a safe disclosure method. “Go somewhere that is somewhat public,” she says. “Look up laws in your state around recording and HIV criminalization. Your partner could use HIV criminalization laws to abuse you through the legal system. If you are legally able to record the conversation so you have proof of your HIV disclosure, it might be helpful to do so.”

If you are on PrEP or any sort of ARV medication and in an abusive relationship, Robin suggests splitting up your medicine supply. “If you have a 90-day supply of medication, maybe only keep 30 days’ worth in your house or apartment,” she says. “Consider giving the rest of your supply to a trusted family member or friend. That way, if your partner tampers with your medication or throws it out, you will still have medication while waiting for a refill.”

Remember: Your HIV and/or STI status does not define who you are as a person. People living with HIV can lead long and healthy lives by taking medicines that keep the virus undetectable. A positive test is an opportunity to treat HIV and stay healthy.

How to help those experiencing DV:

Whether you’re a victim or a concerned friend, opening up about domestic violence is far from easy. “It’s hard to have these conversations,” Robin says. “I think having an open dialogue is the most helpful thing you can do. If you’re concerned about a friend, ask them, ‘How do you feel about your partner? Do you feel comfortable around them? Does your partner make you feel comfortable when having sex with them? Do you have a happy sex life? Has your partner ever tried to go with you to the doctor?’ I like direct questions.”

Continuing to educate yourself is also key. There are many resources available to help you learn more about the cycle of abuse, warning signs, and more.

Resources

- National Domestic Violence Hotline: 24/7 Hotline: 800-799-7233

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence

- National Network to End Domestic Violence: Email Hotline

- National Network to End Domestic Violence: Positively Safe

- National Network to End Domestic Violence: Conversation Guide

Learn More

If you are interested in using PrEP as a tool for reproductive health and wellness and to prevent HIV, go to QCarePlus.com to learn more and speak with a provider today.

*List adapted from The Center for Relationship Abuse Awareness

Joli Ienuso

Joli Ienuso has a Master of Education in Human Sexuality from Widener University, a Bachelor of Arts in Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies from Columbia University, and a MindBody Therapy certification in Embodied Philosophy. Joli provides education in the areas of general professional development, trauma-informed and healing-centered approaches, gender and sexuality equity, normalization of neurodivergence, and loving relationships of all kinds. “I am an empathy enthusiast, contradiction collector, and passionate educator with over a decade of experience,” Joli says. “Some of the identities that inform my social positionally and shape my worldview include being a neuroqueer, Italian-American, non-binary, chronic pain-managing New Yorker.”

Ralston Lockett

Ralston Lockett, APRN, FNP – C, is an advanced practice provider with more than seven years of professional experience serving vulnerable populations. He is a skilled patient advocate with qualified technical nursing skills, including experience working in a high-volume emergency room department and providing primary care and HIV continuum care to diverse populations. Ralston’s areas of particular interest and achievement include migrant health, infectious diseases, health technology, and staff development and training.

Cindy Luquin

Cindy Luquin (she/they) MA, CSE is the founder of PleasureToPeople, Bilingual Sexual Health & Wellness Program. With a decade of experience, Cindy is a certified sexuality educator, focusing on LGBTQ+ sexual health services, professional training, and comprehensive education for bilingual Latinx communities. A passionate advocate, Cindy aims to eliminate disparities through community connection and cultural empowerment. Their mission: Empower through education, bridge gaps, and dismantle barriers for accessible fun and pleasurable well-being. Cindy's influential work has been featured in publications like Cosmopolitan, Teen Vogue, Well + Good, and Refinery29, among others. She currently resides in Maryland with her husband and dog. For more information about Cindy Luquin and PleasureToPeople, please visit: Website: www.pleasuretopeople.com Instagram: @pleasuretopeople

Robin Pereira

Robin Pereira, MPH candidate, is the Positively Safe program specialist at the National Network to End Domestic Violence. Robin has a longtime passion for ending gender-based violence and expanding access to reproductive health care. Her dedication to these missions shines through in her role at the NNEDV. Positively Safe addresses the intersection of HIV and domestic violence. As a specialist, she provides technical assistance, hosts webinars for both domestic violence and HIV advocates, creates tools for NNEDV’s DV and HIV toolkit and curriculum, and presents at local, national, and international conferences. Prior to working on Positively Safe, she supported the NNEDV transitional housing team as coordinator. She graduated from Hofstra University on Long Island in May 2018, with a degree in Journalism and Women’s Studies and a minor in Sociology and is currently pursuing her Masters of Public Health with a concentration in Global Health at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.